The

Downton Abbey Effect

Cottages

and Palaces in “His Red Eminence”

By

Laurel A. Rockefeller

“Downton Abbey.”

Few period dramas have earned the critical acclaim and popularity as the story

of its Crawley family as they navigate the dramatic changes faced in the early

20th century. Featuring lavish estates and stories centred on both

the upstairs nobles and downstairs servants, it can be no wonder so many of us

are excited about the September 2019 release of a theatrical film that continues

the stories of these beloved characters.

Important to

Downton Abbey’s appeal stems from its window into how the upper classes live

and how they interact with the servants whose labours empower their lifestyle.

It’s a time gone by for nearly all of us, a culture few of us experience or

understand. A culture that was very much part of life in 17th

century France.

In “His Red

Eminence, Armand-Jean du Plessis de Richelieu” we are taken through the good

cardinal’s entire adult life, starting at the age of twenty when he was a

student at his beloved Sorbonne. Along the way, he lived in everything from a

spartan dormitory to modest cottages to palaces. Each of these held a very

different lifestyle. Each of them enlightened by watching “Downtown Abbey.” Let’s take a look at his homes.

Du Plessis

Manor/Château Richelieu – Poitou (1585-1594,

intermittent thereafter)

The cardinal’s

childhood home was the medieval manor built by his ancestors and resided at for

centuries. The 16th century Wars of Religion which ultimately

claimed the life of Armand’s father François in 1590 bankrupted the family,

forcing Armand’s mother Suzanne de la Porte to cut what few staff they had before.

Odds are the frugality Suzanne de la Porte imposed on her household meant

Armand grew up with few if any of the luxuries normally enjoyed by the

nobility, a simplicity in lifestyle he maintained for the rest of his life.

Upon the death of his father in 1590, eldest brother

Henri du Plessis became Seigneur de Richelieu. Through political skill and the

kindness of King Henri IV, Henri improved the du Plessis fortunes by convincing

the king to appoint Armand as Bishop of Luçon and with it, a yearly income of

15,000 livres for his brother and, by extension, the family.

(engraving of the

Château Richelieu before its demolition in 1805.)

As Armand’s career improved over the years, he

invested in the family home, transforming it in the Château Richelieu built by

architect Jacques Lemercier, and employing a proper household staff to attend

him whenever he or other family members stayed there. From footmen to

housemaids, valets, and lady’s maids, the château scenes in chapter twelve are

modelled closely after those in Downton Abbey and the many adventures of those

who lived there, both upstairs and downstairs.

Dormitory at the

Sorbonne (1606-1607)

Like most students,

Armand-Jean lived simply in a bedroom that served as bedroom, library, office,

and beyond. He probably shared both a kitchen and lavatory with others living

in the same building. It is the style of life most familiar to us today and

therefore most relatable.

Bishop’s Mansion

– Luçon (1608-1614)

More spacious than

his dormitory, ordination as a priest and investiture as a bishop was a step up

for His Excellency, Bishop du Plessis.

As bishop he lived in a parsonage where he lived, maintained an office

complete with a secretary, and entertained. No less than a cook and a

housekeeper maintained the residence and probably other servants as well,

though likely fewer than ten altogether. Though the sizes of bishop mansions

varied with the wealth and important of individual dioceses, the mansion in

Luçon probably maintained at least five guest bedrooms in addition to the

master bedroom the bishop occupied and those reserved on the top floor for

residential staff.

Mansions – Blois

and Avignon Exiles (1617-1620)

Historically

speaking, we know essentially nothing about where exactly Bishop du Plessis

lived during his years in exile in Blois and Avignon created by his service to

Marie de Medici. As a civil servant, he most likely lived in the same home as

the dowager queen while in Blois. Given Marie de Medici was essentially running

a quasi-independent, rival French government, it is logical to deduce that she

and her staff (du Plessis included) lived in a modest mansion sufficiently

sized to accommodate a household of at least thirty and probably closer to

sixty. Upon being ordered away from de Medici in the form of being sent to

Avignon, Bishop du Plessis and those exiled with him probably experienced a

more scaled down version of his life in Blois with a smaller mansion-prison and

fewer staff, but still attended somewhat by cooks, housekeepers, and perhaps a

footman or two whose real function was to enforce the house arrest while spying

on the prisoners.

Parisian

Cottages (1614-1617, 1620-1629)

In September, 1614

Bishop du Plessis arrived in Paris as a delegate from Poitou representing its

clergy at the meeting of the Estates-General in Paris. Though we know nothing

about how or where the bishop was housed, it was most likely a modest cottage

not unlike Crawley House in Downton Abbey. The bishop probably had a cook and a

housekeeper to look after him. Upon being appointed to the large stream of

government positions showcased in “Eminence” that staff level would have slowed

increased, but rarely exceeding more than five or ten total servants plus or

minus the red guards who protected his person. These cottages probably looked

and felt a great deal like Crawley House, modest but comfortable, but better

suited to city life than the rural-centric Crawley House.

Apartment at the

Louvre (intermittent, 1622-1629)

Living at the

Louvre was a special honour granted as a reward to favourite courtiers. It was

also given to those ministers the king wanted kept close to him—either because

he wanted him closely watched and/or because he needed that minister available

to him at all hours of the day and night.

As seen in

“Eminence,” Richelieu most likely divided his residency between an apartment in

the Louvre and a nearby cottage. While staying at the Louvre, housemaids would

have kept his apartment tidy and cooks would have provided him with his meals.

Footmen summoned him into the royal presence.

Following his 1628

success at La Rochelle, King Louis XIII gifted him with his own estate mere

metres from the Louvre which Richelieu designed with architect Jacques

Lemercier, the Palais Cardinal, a grand home that survives to this day as the

“Palais Royal.”

Palais Cardinal (1629-1642)

In 1629 Jacques

Lemercier completed the Palais Cardinal, the ultra-modern palace estate which

became Cardinal Richelieu’s principle residence from 1629 until his death on 4

December, 1642. The Palais Cardinal featured Paris’ first theatre at which the

many plays Richelieu penned were performed. Though the cardinal maintained the

simple lifestyle one expects of a parish priest, he spent generously on a

massive household staff at the Palais Cardinal. With an income exceeding two

million livres per year at the end of his life, he could afford it. But as with

everything else, his spending was far more about the principle than his own

needs or interests. In patronizing the visual, dramatic, and musical arts at

the Palais, he fostered French culture in ways he believed were essential to

the longevity of the State. In offering employment to a far larger household

staff than he needed, he invested in his community.

In the end,

Armand-Jean du Plessis, cardinal and duc de Richelieu was not the mean-spirited

and heartless villain of the Dumas novels, but rather the kind, extremely

generous, and far-sighted statesman who invested in people, in the arts, in

long-term diplomacy, and in a strong, unified France. Instead of using his

income from government service for his own creature comforts and agendas, he

invested in the French people, in French culture, and in the French State.

The fictional Earl

of Grantham considered himself the custodian of Downtown Abbey. The very real

Cardinal Richelieu made himself the custodian of France itself. Few ministers have done more or served better

than His Red Eminence, Armand-Jean du Plessis de Richelieu.

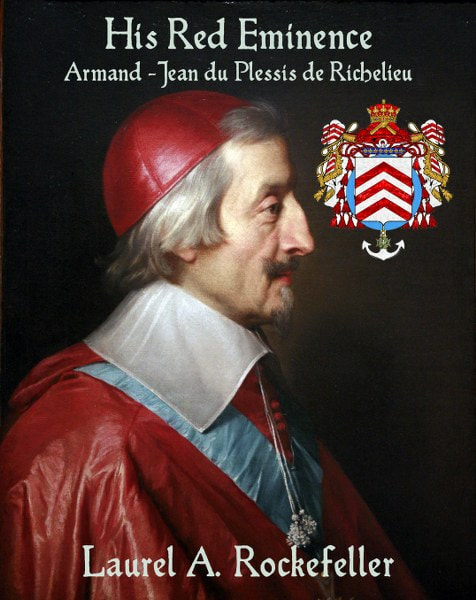

His

Red Eminence

Armand-Jean

du Plessis de Richelieu

by

Laurel A. Rockefeller

Genre:

Historical Fiction

Priest.

Lover. Statesman.

From

the author of the best-selling “Legendary Women of World History”

series ...

Cardinal

Armand-Jean du Plessis, duc de Richelieu is one of the most famous --

or infamous politicians of all time. Made a villain in the popular

Dumas novel, "The Three Musketeers," the real man was a

dedicated public servant loyal to king and country. A man of logic

and reason, he transformed how we think about nations and

nationality. He secularized wars between countries, patronized the

arts for the sake of the public good, founded the first newspaper in

France, and created France as the modern country we know

today.

Filled

with period music, dance, and plenty of romance, "His Red

Eminence" transports you back to the court of King Louis XIII in

all its vibrant and living color.

Includes

eight period songs, plus prayers, a detailed timeline, and extensive

bibliography so you can keep learning.

Born,

raised, and educated in Lincoln, Nebraska USA Laurel A. Rockefeller

is author of over twenty books published and self-published since

August, 2012 and in languages ranging from Welsh to Spanish to

Chinese and everything in between.

A dedicated scholar and

biographical historian, Ms. Rockefeller is passionate about education

and improving history literacy worldwide.

With

her lyrical writing style, Laurel's books are as beautiful to read as

they are informative.

In

her spare time, Laurel enjoys spending time with her cockatiels,

attending living history activities, travelling to historic places in

both the United States and United Kingdom, and watching classic

motion pictures and classic television series.

Follow

the tour HERE

for exclusive excerpts, guest posts and a giveaway!

X